Working entirely "off the wheels" is possible only in theory. In practice, a half-hour delay in the raw material supply can trigger a half-shift stoppage. Therefore, the accumulation and storage methods of raw materials play a critical role in the processing technology and, sometimes, in business survival. In planning wood processing production, it's crucial to decide during the design phase how wastes will be collected and transported. There are only two options: either they are removed by a single conveyor system to storage, or they are locally collected and removed by wheeled transport. This affects the layout of the raw material exchange, sawing shop, wood dryers, gluing shop, boiler house, and other facilities significantly.

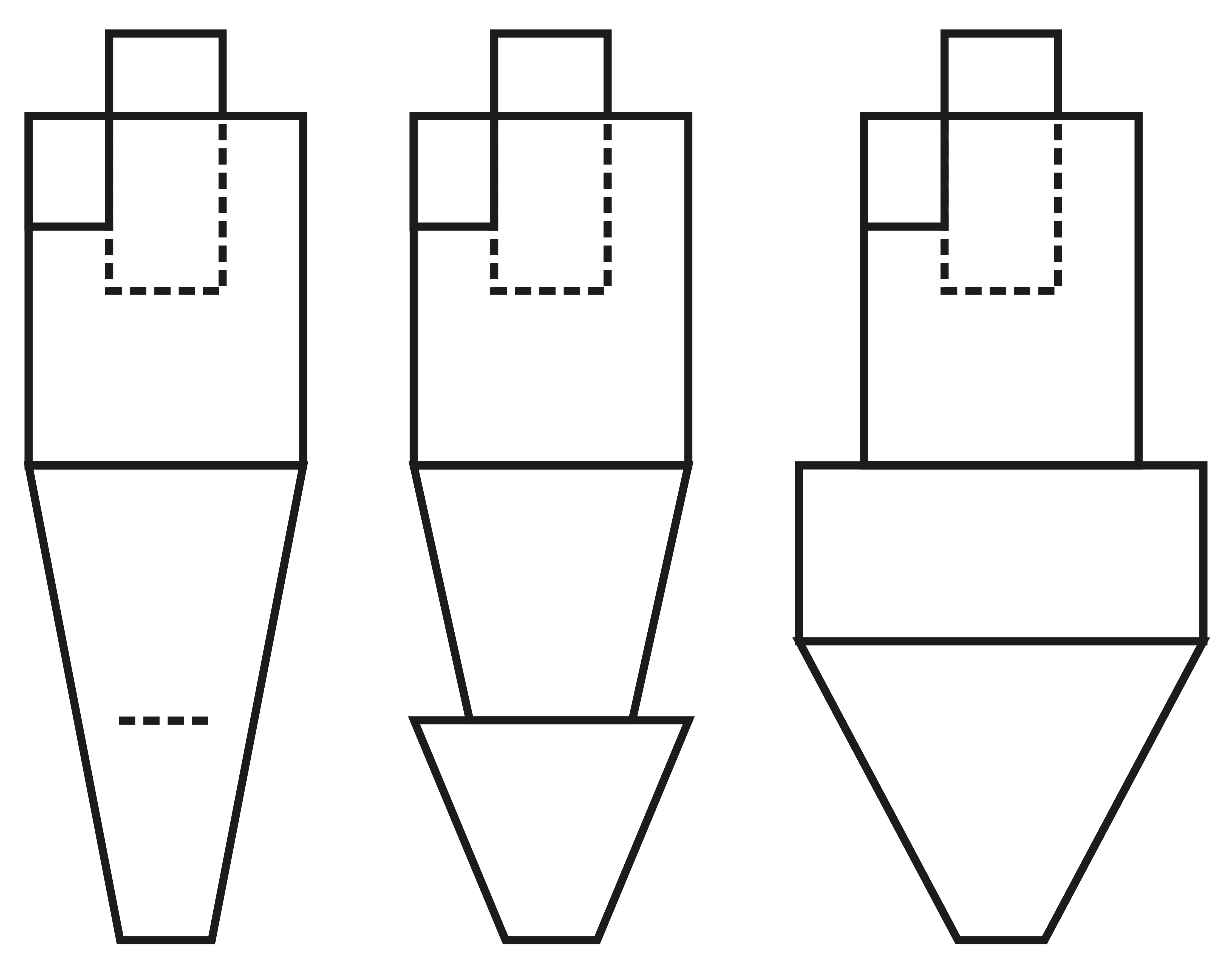

Using centralized conveyors significantly increases the overall cost and complicates the layout but offers substantial savings by eliminating weather and human factors. This approach is most justified in large enterprises where processing is measured in tens and hundreds of thousands of tons of raw materials per month. Often, equipment in such facilities is arranged on multiple floors, saving production space and reducing the overall conveyor length by installing gravity chutes. In such cases of wood processing, machines with large and powerful cutters are used that transform logs into cant while converting excess wood directly into small chips, bypassing the production of slab wood. Shredders and chippers are installed near other machines to drop shredded waste onto a single conveyor. A significant advantage of this system is that all operations take place indoors or in covered conveyors, minimizing the chance of soil, stones, snow, and other unwanted contaminants. The wood material quality is maximized, as debarking machines are usually installed at the technology chain's entry point, removing all impurities with the top layer. The downside of this approach is that if, for any reason, the unified waste disposal stops, the entire plant's operations must halt, leading to significant losses. Separate waste outputs and emergency small storage facilities are provided for such cases, where waste is moved by front loaders and dump trucks.

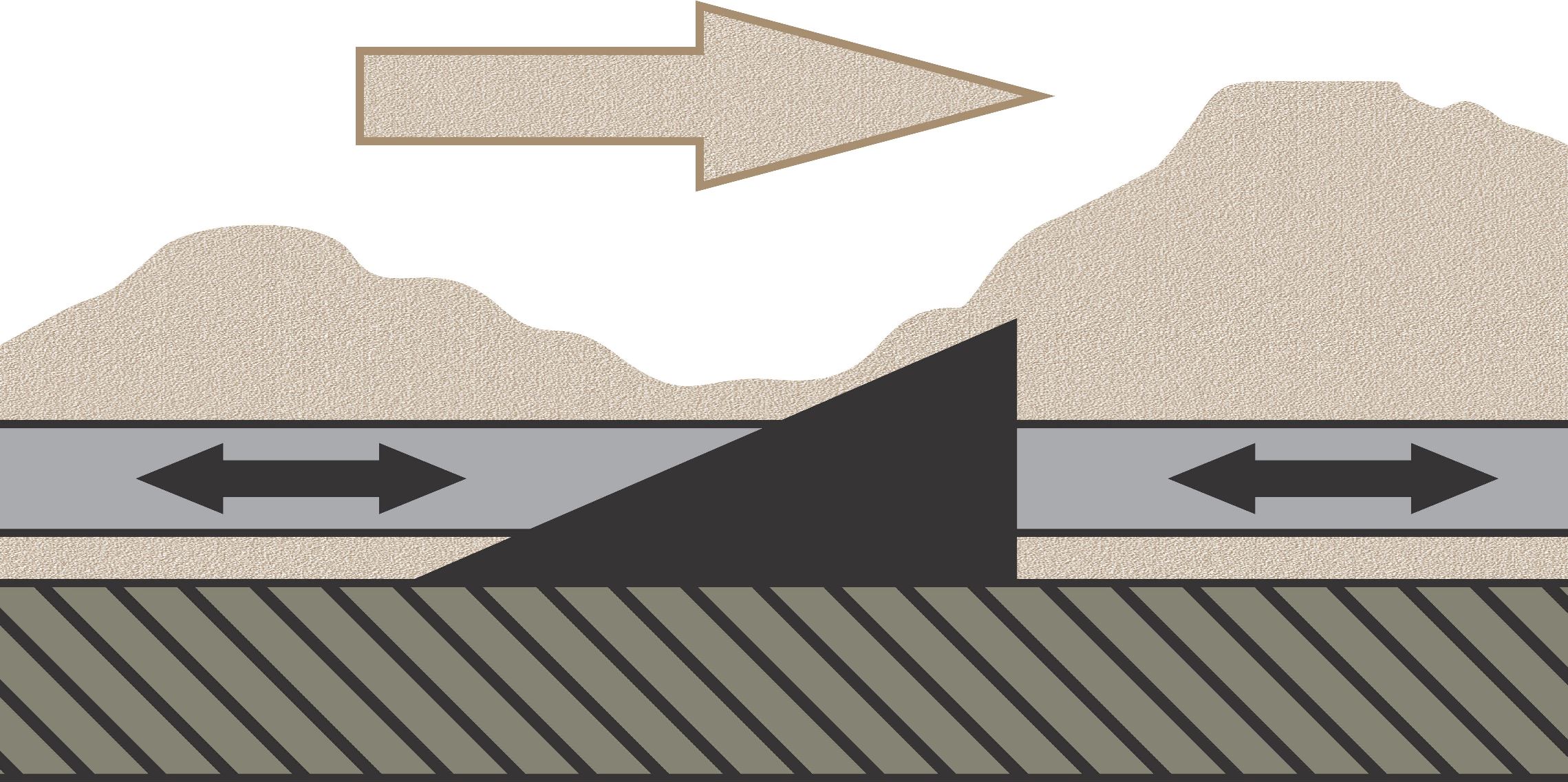

More commonly, a pellet plant is appended to an existing facility with its established logistics, and as production tempo increases, each waste collection site turns into a small apocalypse. Typically, sawdust and chips are regarded as waste, not beautifying the sites, and are dumped directly on the ground. These piles also become depositories for tin cans, worn-out parts, and packaging debris with nails. These items subsequently get mixed by wheels into a single mass, creating a swamp, unsanitary conditions, and other karmic implications. Notably, a few months after the pellet plant's launch, there was a day of significant wear on crushers and the pelletizer's die; operators couldn't stabilize the equipment. It turned out the loader driver, following instructions to "clean the dump area," loaded the pellet plant with everything left, including construction debris when sawdust ran out.

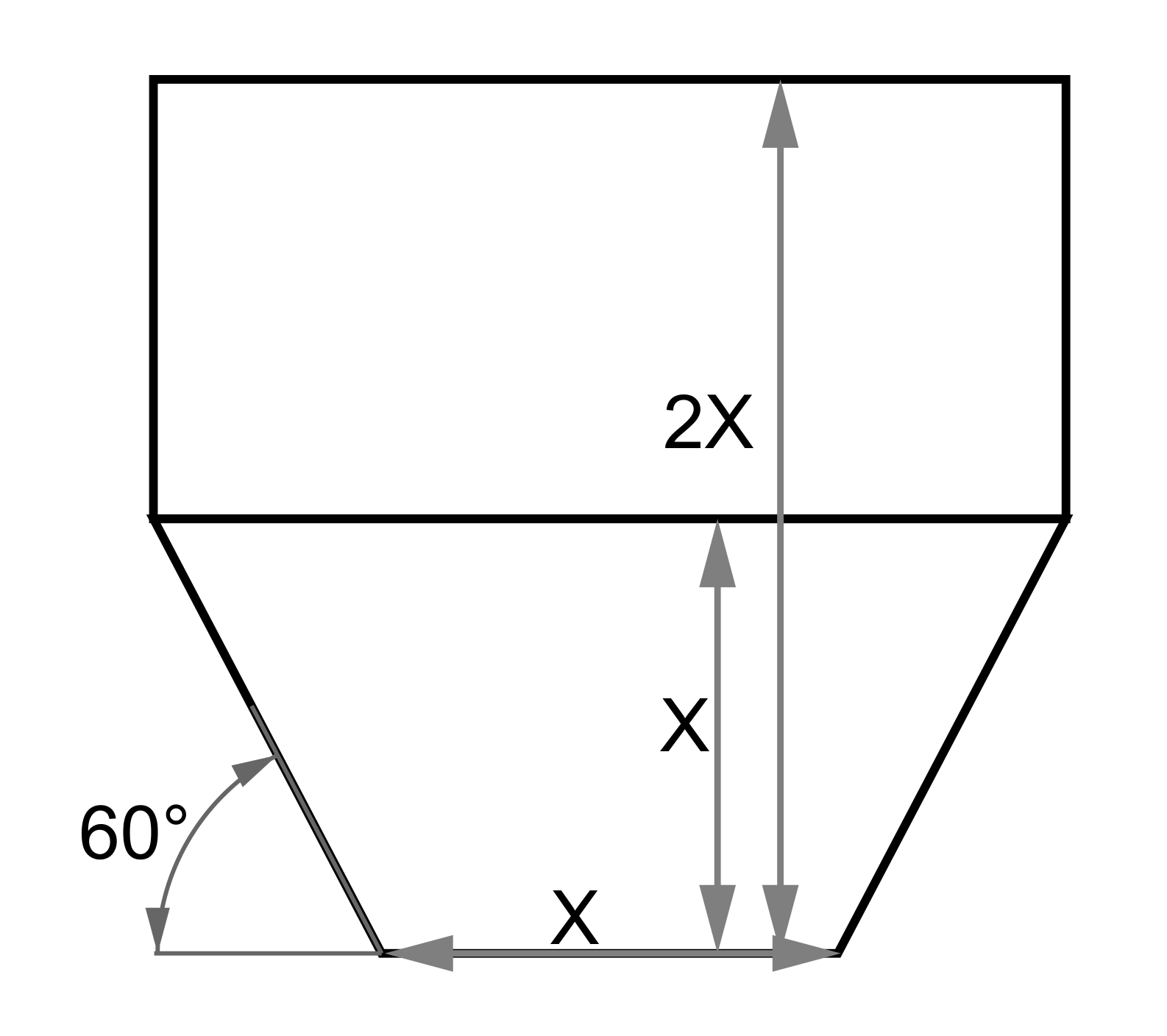

Undoubtedly, the cheapest raw material storage method is in an open area. If the region doesn't see a lot of precipitation and strong winds, storing this way for several weeks or months is acceptable for raw wood. However, even large open areas are much cheaper to enhance with a proper covering in advance. The best landscape design is asphalt and concrete.

For broken pallets, chips derived from them, sunflower husks, bales of straw, or wood shavings, a covered warehouse is necessary. The formation of layers with different moisture levels can completely disrupt the steady operation of the plant, even with a drying complex in place, and sharply reduce product quality. Where possible, raw material warehouses are also built for wet wood, as slab wood naturally dries fairly quickly to 30-40% moisture, while the top layers from a pile with frozen snow on them afterward form excessively wet chips that cannot dry simultaneously with the main mass.

If no weight control is established at the entrance to the industrial zone, it is impossible to precisely determine the mass of raw material. The only method is to separate by piles and perform a control measurement based on the output product both in terms of volume and quality. Moisture control in sawdust using usual grain methods is minimally informative due to the heterogeneity in batch volume and across different climatic seasons. It's much easier to judge the quality of raw material during processing, by determining the moisture in the bin of pre-ground chips and checking for separable foreign impurities.

In transporting raw materials from sources to the pellet plant site, communication skills and a comprehensive approach are crucial. It is much cheaper and more reliable to invest in setting up a temporary storage facility at the starting point than to heroically struggle at various stages of cleaning and moisture leveling. The simplest method is to install a dumpster under the cyclone of the enterprise's aspiration system. The existing cyclone supports are covered with profiled sheeting, and on the transport feed side, fix a tarpaulin curtain on a thick stainless steel cable. Checking and repairing the aspiration system outside the premises will be beneficial. This upgrade can completely prevent precipitation and foreign impurities from entering and allows for quick removal of raw materials without using a front-end loader.

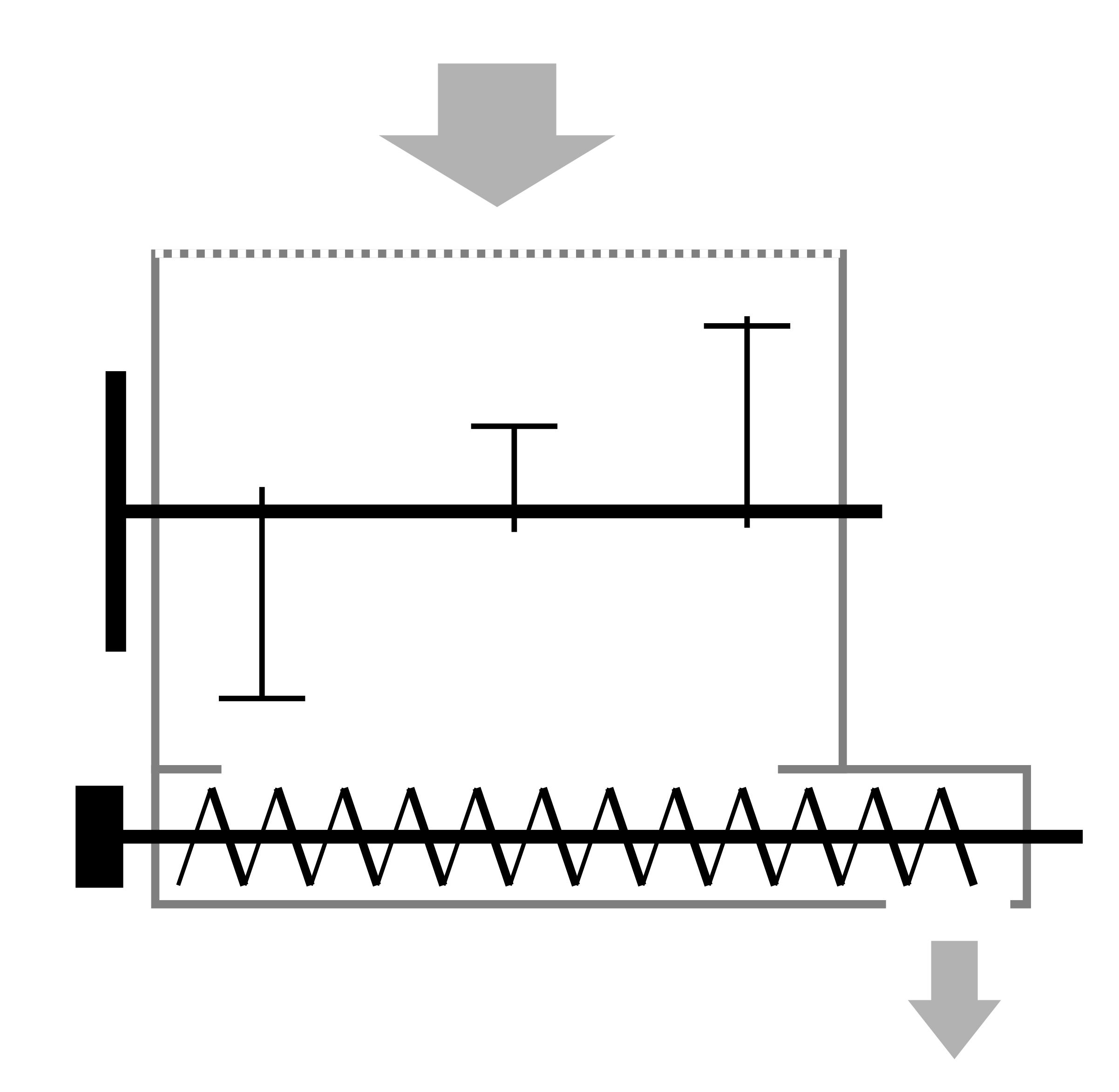

Transporting slab wood on logging trucks is the most thankless task. Each year machines improve, and material savings increasingly come to the forefront. From a log, the maximum number of useful blanks is sawn. The remaining slabs are often mixed with so-called "noodles" - sticks so thin that at natural moisture content they can bend and even tie into knots like rope. Such waste, once loaded onto a logging truck and subsequently unloaded, becomes tightly entwined, making automatic feeding into a chipper impossible. Spreading the pile with pike poles on the feed table is ineffective and hazardous for personnel. There are only two popular solutions to this problem: either installing a special all-eating and quite expensive shredder on the pellet facility, or funding the completion of source material chippers. The second option is feasible when slabs and cuttings are removed from the sawmill on a single conveyor. If all incoming raw material arrives in bulk form, the pellet production manager has far fewer concerns.

Another important point: the acceptance of waste should be charged. No matter how severe the situation with environmentalists and dumps, even with strong administrative pressure, there should be at least a minimal fee for accepting waste. At a negative raw material cost, owners continue to see it as a problem. As soon as they manage to get a couple of dollars per truck under the pretext of "at least for candies for the driver," that's it. Waste becomes valuable raw material, and the price for it will increase until it absorbs all the profit from biofuel production.